How Iowa's virus battle began | COVID Cause & Effect, Ep. 1

Local 5 breaks down the novel coronavirus pandemic and how it has impacted Iowans over the last year.

As of March 7, 2021, 339,544 Iowans have tested positive for the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, better known as COVID-19.

Recoveries total 320,055.

5,558 Iowans have lost their battle with the virus.

But as the calendar turned from 2020 to 2021, the state's vaccine journey began.

More than 864,000 vaccine doses have been administered in Iowa, with 833,624 being given to Iowans.

The road to recovery began immediately following Iowa's first three confirmed cases on March 8, 2020, but there is still much to do before any sense of normalcy is back.

Local 5 is breaking down, from the beginning, the impact that COVID-19 has had on the state.

Watch "COVID Cause & Effect" on-air, online and on the We Are Iowa app Monday-Friday night at 6 p.m.

The beginning From 3 cases to thousands

The United States reported its first COVID-19 case on Jan. 21, 2020. Three days later, Illinois reported its first case.

During this time, Iowa started preparations, including seminars for schools and businesses to learn about what to do in case an outbreak occurred.

On March 6, Nebraska reports its first case, closing in on Iowa.

Gov. Kim Reynolds orders partial activation of the State Emergency Operation Center (SEOC) the next day.

"We knew I think, from the very beginning, this was going to be serious. I don't know if we thought it would last a year, but we knew it was going to be serious," Reynolds told Local 5's Rachel Droze in an interview last month.

And then, on March 8, Iowa confirmed three individuals in Johnson County tested positive for the virus after coming home from an Egyptian cruise. Reynolds signs a Disaster Proclamation in response to the new cases.

"I don't know if you're ever ready for an unprecedented, historic pandemic," Reynolds said. "I'm not sure you can ever be prepared and, the thing with this pandemic is, the information has changed so much over time so you have to be flexible and be able to adjust and move with it."

"We had a really tough 2019 and people just completely forget that because of the pandemic. It's hard to believe it's been a year. I mean, sometimes I ... it feels like 10."

To watch the full interview with Gov. Reynolds, click here or view on YouTube below

Days later, colleges closed down. All three of Iowa's public universities move to online classes by March 11, the same day the World Health Organization characterizes COVID-19 as a pandemic.

Less than a week after the first three cases were confirmed, Reynolds announced community spread in the state.

Her administration recommended schools to close for four weeks, but did not mandate it.

On March 16, the Iowa Legislature closed down in the middle of session. The next day, the rest of the state is mandated to shut down.

Just one week after the state shut down, the state confirmed its first death from the virus, an older adult, 61-80 years old from Dubuque County.

During the week of March 24, Reynolds ordered retail stores, salons, bars, tattoo parlors and more to shut down. Non-essential surgeries were halted, and hospitals started limiting visitors.

Then in April, Iowa saw its largest one-week spike in unemployment rates.

Reynolds and her administration introduced Regional Medical Coordination Centers on April 7, detailing more information about Iowans battling the virus from inside hospitals.

Throughout April, the governor's administration provided Iowans with updates on outbreaks at long-term care facilities, which house those most vulnerable to the virus.

Then, the entire country experienced personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages.

"I made phone calls to source PPE, my CFO at DHS was making phone calls late in the evening – weekends – to source PPE," said interim Iowa Department of Public Health Director Kelly Garcia, who is also the director of the Iowa Department of Human Services. "It really was it was an all-hands-on-deck effort. Every state agency was engaged. We were highly coordinated and working on getting supplies into Iowa. I think we did.

"Ultimately, we were able to, but those were scary times."

Garcia started at DHS in Nov. 2019 and was tagged in to serve as interim IDPH director in August 2020. She was later confirmed a permanent director of IDPH.

"We've tried really hard to provide that information in real-time; real, accurate, clear information to Iowans, but it is ever-changing because we're learning more and we're learning more every day," Garcia said. "So that's been a balance. We don't want to jump the gun and explain something before we're ready to really explain it and understand it ourselves and understand the impacts it has on Iowans."

"I was looking at the residents and our facilities. I wanted to make sure that they were safe, that my employees were safe and we were still able to take care of children in need of assistance and do our work. So, we worked around the clock to make that happen."

To watch the full interview with Iowa DHS/DPH Director Kelly Garcia, click here or view on YouTube below

COVID hit Iowa's meatpacking plants with devastating force. The spread of the virus happened quickly, forcing some of these plants to close for cleaning, threatening the country's food supply.

Reynolds and Iowa Department of Education Director Ann Lebo announced all schools must close for in-person learning for the rest of the year.

That happened on April 17.

"Knowing what I know now, I probably would not have closed the schools," Reynolds said. "Community spread at that time meant three to four cases in one area, and so we did what almost every other state did and we closed our schools down and then started some closures after that. Very targeted and mitigated, but still, I probably wouldn't have done that if I'd known then what I know now."

Just a few days later on April 21, TestIowa launched to administer thousands of tests a day. The website still allows Iowans to schedule free appointments to get tested for COVID-19.

Many saw the rollout as shaky, reporting issues with test availability and access.

As cases started to decrease slightly, Reynolds and her team announced plans to reopen the state. Elective surgeries and farmers' markets were set to start in May, even though cases and deaths from the virus continued.

Woodbury County, located 100 miles east of Omaha, was one area in Iowa hardest hit early on.

"When we got hit, it was like a waterfall,” said Tyler Brock, deputy director of the Siouxland District Health Department. “It was a flood and, frankly, we were not ready."

According to U.S. Census data, about 100,000 people live in Woodbury County.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the Sioux City area is largely made up of blue-collar workers.

The Dakota City Tyson plant, located just over the Nebraska border, is one of the area’s major employers. In April, a COVID-19 outbreak temporarily shut down the plant.

"Once it started in that population, we didn't feel like it was going to stop anytime soon,” Brock said.

Tyson idled the plant for six days to deep clean and test their 4,300 employees.

Hospitals, around that time, were stretched thin and because of that, Dr. Larry Volz, chief medical director at MercyOne Siouxland Medical Center, said he felt Tyson should have idled sooner.

“I felt like, especially at the time, production should have stopped earlier,” Volz said. “That's just my opinion. I think at the time that we finally stopped production, the virus had already been rampant. We had already surged.”

Treatment protocols for COVID were still being investigated, so doctors were unsure if the care they were giving was helping or hurting.

“[We were] learning a lot of what [we were] doing, from a treatment standpoint, from Facebook COVID groups for physicians,” Volz said. “We were learning what they thought was working in New York at an ICU and trying to implement the same thing here. We were redirecting and pivoting based on data and information coming out from CDC or from other studies. A lot of it was really just doing the best you can with the knowledge we have.”

The elderly and those with underlying conditions are most likely to get seriously ill or die from COVID, but Volz said in late April and early May, many patients in the hospital didn’t fit that description.

“When we were seeing a 48-year-old Hispanic male come in from the meatpacking plant and going on a ventilator, those were those were really scary times,” Volz added. “[We were thinking], ‘If these young, healthy people are getting sick from this, what is this really going to end up being?’”

Back then, personal protective equipment was in short supply, and doctors in Woodbury County were competing with the rest of the world.

"I can't have my nurses in the ICU taking care of a COVID patient wearing a homemade cloth mask hoping that they're going to stay protected,” Dr. Volz said.

Volz said there was a time he bought the entire supply of painting masks from a local store.

“I remember me and one of my daughters driving to Home Depot and buying all the N95s and face shields that they had because it was the only place that we could get them before the community bought them,” Volz said. “We filled up the back of my pickup truck with painting masks because we weren't sure we were going to have enough PPE to get through."

Data on the Siouxland District Health Department’s website shows Woodbury County had 25 new positive cases reported the week of April 19. At the time, that was the most cases reported in a single week.

The following week, that record was shattered, when 448 new cases were reported.

Then, the week of May 3, the record was broken again with 667 new cases reported.

"We went from testing 10-20 people in the whole community every day to doing 400-500 tests in a community testing clinic in one day with a really high number of those people being positive,” Brock said. “We weren't ready for it. We weren't ready for that kind of volume."

The summer of nothing Iowans continue on

The summer of COVID was pretty uneventful, mainly due to notable events being canceled due to gathering restrictions.

No Iowa State Fair. No 80/35 or Hinterland. And no RAGBRAI.

Cities across the state weighed their options for Fourth of July celebrations, some canceling altogether.

In late July, COVID data collectors noticed changes in the data released from the state. Positive tests were added to days from March, and so were deaths.

The disruption in the data didn't go unnoticed, and reaching officials from the Iowa Department of Public Health became difficult.

Now-former spokeswoman Amy McCoy confirmed the state was backdating certain data in July, but the state wouldn't announce it to the public until late August.

And then, on Aug. 10, the derecho.

A summer of nothing slipped into a summer of chaos across the state, where already-struggling Iowans had to face another obstacle.

Once August hit, Reynolds pushed harder for kids to get back into the classroom, and public universities opened their campuses back open for students.

Little did Iowans know what would lie ahead in the fall.

Here's what we've verified during the pandemic so far

The surge The longest fall of all

At first, cases ticked up in specific counties with larger populations, like Polk, Johnson, Story and Black Hawk.

Three of those counties—Johnson, Story and Black Hawk—are homes to Iowa's three public universities. Reports of students packing bars and having house parties circulated on social media.

Gov. Reynolds instilled intermittent closures for specific counties seeing surges in September, but with temperatures slipping lower, Iowans were moving their social gatherings inside.

By November, hospital systems across the state were pushed to the brink. More people tested positive, more people were sent to the hospital to just be told to go home to get through the symptoms.

Hospitalizations peaked at over 1,500, with total hospital admissions at 5,349 for the month.

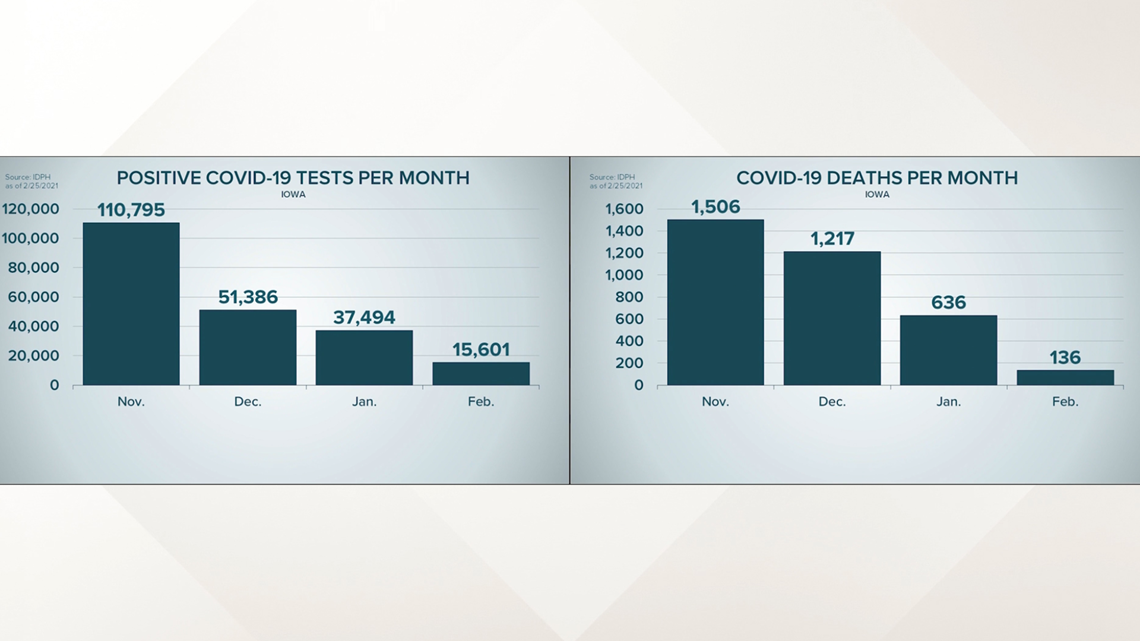

A total of 1,506 Iowans died in November, not knowing that 2019 would be their last time to gather with family for Thanksgiving or the holidays.

Long-term care facilities, where some go to live out the rest of their lives in comfort, turned into every family's worst nightmare. At the peak of the surge, there were at least 90 LTC facility outbreaks.

On Nov. 16, Gov. Reynolds turned to prime-time television to do something she said she wouldn't do: mandate Iowans to wear face masks while in public settings.

She also ordered brand-new closures among bars and restaurants, as well as gathering restrictions for sporting events.

The virus taking less of a toll on some was not enough.

"But I'm afraid that these mild cases have created a mindset where Iowans have become complacent ... where we've lost that sight of what it was, why it was so important to flatten the curve," Reynolds said at the time.

Watch: Gov. Kim Reynolds' Nov. 16, 2020 COVID-19 address

A little bit of hope, but still a lot of worries Vaccines and variants

Most Iowans must have listened, because what many were expecting to be an even worse surge in December turned into a dip in positive tests and hospitalizations.

Reynolds even loosened restrictions on bars and restaurants on Dec. 16.

Iowans breathed a collective sigh of relief when the Food and Drug Administration announced the first COVID-19 vaccine, developed by Pfizer, was approved for emergency use on Dec. 11.

Pfizer vaccine doses shipped out for the week of Dec. 14, heading to long-term care facilities and hospitals to vaccinate residents and health care workers.

A week later, the Moderna vaccine would be clipped onto the coronavirus-fighting toolbelt.

But then the next blow hit: variants.

A variant that spreads faster than the original strain originated in the United Kingdom. The B.1.1.7 variant forced the UK to go on lockdown again in December.

Two other variants also threaten the globe, one originating in South Africa (B.1.351) and the other originating from Brazil (P.1).

Iowa confirmed three cases of the B.1.1.7 variant on Feb. 1. Neither the B.1.351 nor P.1 variants have been confirmed to be in Iowa.

Vaccine rollout appeared to start off smoothly in Iowa among health care workers and long-term care residents and staff.

But confusion on eligibility flooded local health departments and Local 5's newsroom with phone calls and social media messages after the state reported it wouldn't receive as many doses as initially planned.

The Trump administration said the numbers were adjusted once officials received the actual number of doses Pfizer had to ship.

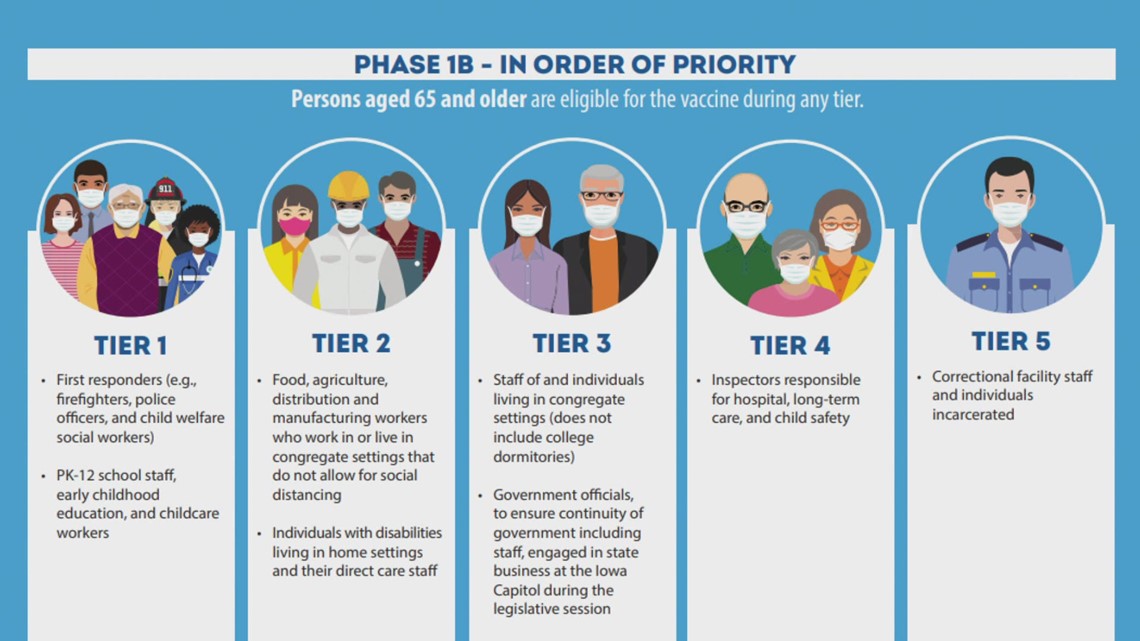

On Jan. 12, 2021, IDPH released the Infectious Disease Advisory Council's recommendations on who should be next for the vaccine, with Phase 1B scheduled to start on Feb. 1.

Initially, Iowans 75 years and older, as well as high-risk individuals, were supposed to be listed in Phase 1B. High-risk individuals included individuals with disabilities living in home settings, correctional facilities, other congregate settings and meatpacking plants were just some of the examples from the IDPH.

But on Jan. 21, the state released an updated plan that included Iowans 65 years and older and a five-tiered plan.

Phase 1B Tier 1 officially started on Feb. 1.

A few days later, the new Biden administration announced increases in vaccine allocations. Reynolds confirmed the news on Jan. 27.

The supply did not meet the demand, but Iowa pharmacies were ready to start vaccinating.

Older Iowans were told to reach out to their local Area Agency on Aging (AAA) to find assistance in scheduling vaccine appointments on Feb. 4, but the next day, Local 5 was told they couldn't do that.

Older Iowans struggled to obtain vaccine appointments and said it felt like they were "competing" for the vaccine. Public health officials urged patience.

The state announced moves to create a statewide scheduling system and vaccine provider locator for Iowans to easily access their appointment. Then, the state split the contract in half, hoping to partner with two different companies to create two different systems.

The state announced they selected Microsoft on Feb. 9, but eventually scrapped the plans for both systems.

Also during February, the Reynolds administration removed mitigation requirements from the Public Health Disaster Proclamation such as face mask usage and gathering limits.

Democrats claimed the administration didn't consult with IDPH ahead of the announcement.

Across the country, chilling temperatures halted vaccine shipments, and many providers had to cancel vaccine appointments due to conditions.

Counties that didn't meet the 80% threshold of vaccine administration were told they wouldn't receive their allotment for the week of Feb. 15. The state backtracked on the following Monday.

During all of this, Iowans took it upon themselves to find vaccine appointments for eligible folks.

Eventually, Reynolds announced the state's already-existing 2-1-1 call center would assist older Iowans with scheduling vaccine appointments starting March 9.

1 year later Where do we go now?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends people continue practicing mitigation efforts to limit the spread of the virus and to get a vaccine once it is available.

Those mitigation efforts include:

- Washing hands frequently

- Wearing a face covering

- Maintaining six feet of social distance

- Avoiding indoor gatherings

- Staying home when sick

There are now three different vaccines available to Americans: Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson. J&J is the only single-dose vaccine while the others are two doses.

Health officials recommend getting the first vaccine available to an individual. All meet efficacy requirements that limit the severity of illness and dramatically reduce the chance of hospitalization and death.

"We are not done with this pandemic, and that as Iowans, we need to band together to really look for those who are vulnerable and then send them our way because we have resources ready to get them the help that they need," Garcia reflected. "Now is the time to be neighborly and kind. This is going to take a long time to really recover, but we're well on our way."

And starting Monday, March 8, vaccine eligibility in Iowa expands to those with underlying medical conditions.

Watch: Iowans find the joy in everyday life, despite the pandemic