COLLECTION: The impact of Black history on Iowa sports

Local 5 Sports Director Reina Garcia takes a closer look at the lives and legacies — both on and off the field — of these three Black athletes in Iowa history.

Duke Slater, Johnny Bright and Jack Trice are names many in Iowa may have heard of. But do you know the stories behind these historic Black athletes and the impact they had on the state?

Local 5 Sports Director Reina Garcia takes a closer look at the lives and legacies — both on and off the field — of these three men.

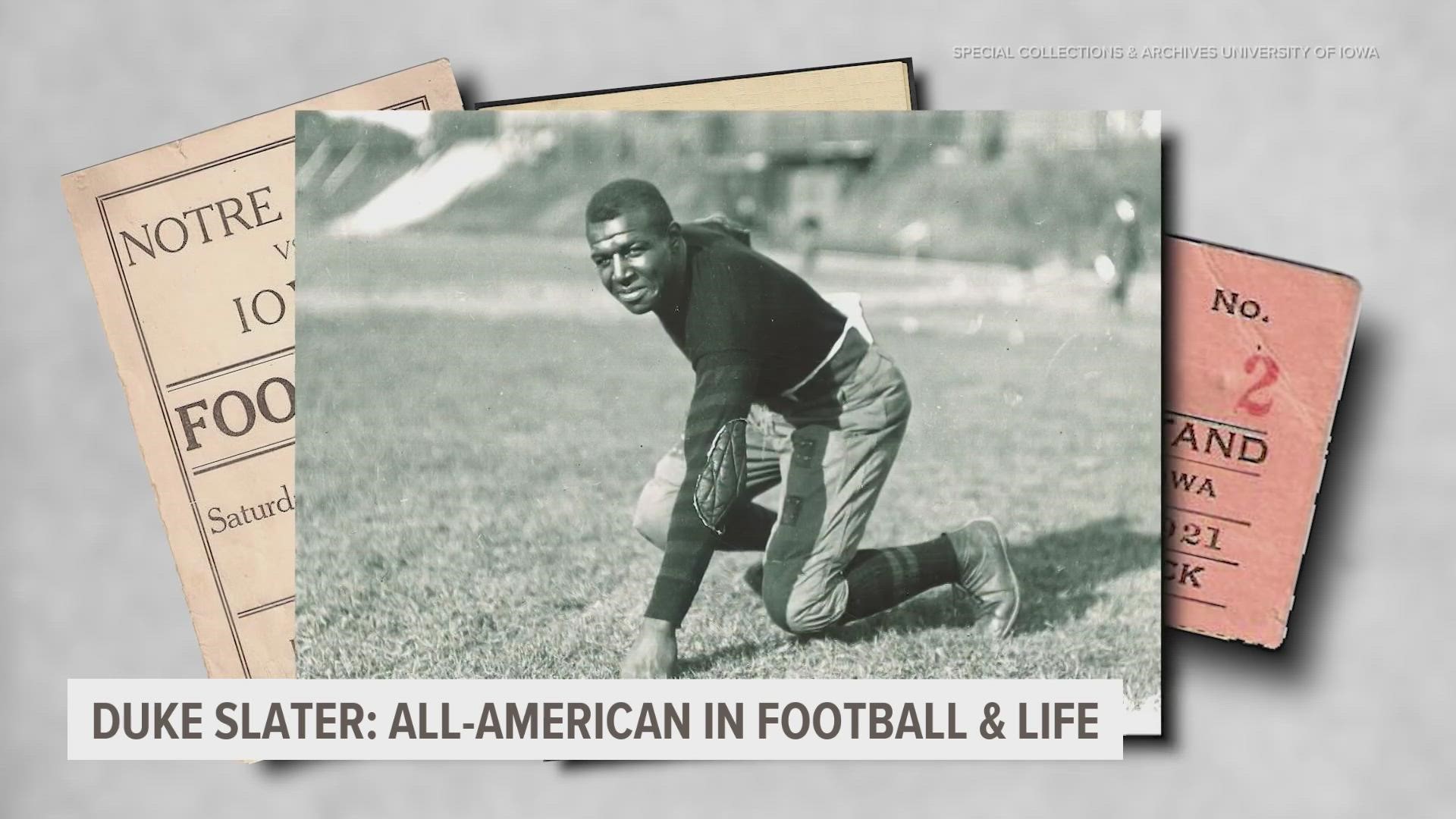

Duke Slater

In the small town of Clinton, the legend of Frederick Wayman Slater — better known as Duke Slater — began to form.

Duke and his family moved to the area when he was 13 years old, and he made his mark in more ways than one.

Some still remain to this day.

On the football field, Duke was a spectacular talent and helped Clinton High School win two state championships. Off the field, he was a well-rounded student.

"He was a very good student here. He was also in the drama club. He performed in a couple of plays," said Bill Misiewicz, a teacher at Clinton High School.

His can-do attitude and joyous spirit made him well-liked by many of his peers, with author Neal Rozendaal sharing about his public persona.

"Duke Slater had a tremendous personality. People really loved him. When people were around Duke Slater, they couldn't help but like him, and I think particularly when he was playing football," Rozendaal said. "To be a Black man in that era playing football, he faced a lot of prejudice. There were a lot of late hits and cheap shots and things of that nature."

Rozendaal wrote a biography on Duke's life and legacy.

"They said that the smile never left his face. He was always someone who just always had good humor and he was able to diffuse situations that might have been problematic for other people, both because of his personality but [also because] most of the time, he was the strongest person on the field. And those things, he was able to use to battle the prejudice of the time," he added.

Duke's talents led him to the University of Iowa, where he played football from 1918 to 1921. During his time as a Hawkeye, he was a three-time All-Conference Selection and a two-time All-American.

During a time where racism created constant barriers for African Americans in all aspects of life, Duke continued to defy the odds and blaze a path for other Black players to follow.

In 1922, Duke became the first African American lineman in the NFL and

went on to play 10 seasons, where he was a seven-time all-pro.

"He was a terrific football player. He really was in his day widely regarded as one of the greatest lineman to ever play the sport," Rozendaal said.

That's what Duke is best remembered for, but what he went on to achieve after his football career was just as remarkable.

Duke pursued a law degree from the University of Iowa while he was still in the NFL. After earning his degree in 1928, he went on to become a lawyer and practice in the Chicago metro.

About 20 years later, he became the second African American judge elected to the Cook County Municipal Court — and by 1960, he became the first African American judge elevated to the Chicago Superior Court.

Through all this, Duke was actively working for the advancement and empowerment of minorities in the united states.

"He was advising president Truman to create the Fair Employment Practices Act in 1948. He was also instrumental in advising the president to ban segregation in the armed forces which was a tremendous step after World War II of creating democracy not only for Europe but also here in the United States," said Duke's coach, Francis Boggus.

Boggus, who also is part of the Clinton County Community Hometown Pride Committee, said that Duke was an activist through and through.

"[He] put the words of the constitution into actual effect and how they affected minority groups who were being discriminated against, it gave them a vehicle to be heard and acknowledged their importance and dignity as human beings," Boggus said.

Duke's community was always at the center of everything he did, and he made it a point to give back and mentor the next generation.

"He's someone that, in every aspect of his life, strived to be the very best he could, and I think he should be looked upon as a beacon of hope," Boggus said.

For a while, it seemed Duke's legacy was being forgotten with every passing year.

But the Duke Slater Memorial Statue Committee is making sure his legacy lives on in Clinton.

They're installing a life-size statue of Duke across from Clinton High School.

"The statue will be overlooking the football field which we think will be an aspiration for young people seeing that and saying if he can achieve it, I can achieve that too," Boggus said.

In addition, they'll be establishing a scholarship fund in his name.

You see, playing football was what he did — but it didn't define who he was.

"Who he was and what he was, that's more important than making a special block to win the big game against Notre Dame and being one of the greatest Hawkeyes of all time. Again, this is a man of huge character, and this is something our community should be able to hang our hats on." Misiewicz said.

Whether it was on the field, in the courtroom or spending time with people in his community, Duke's character always has and will continue to shine through.

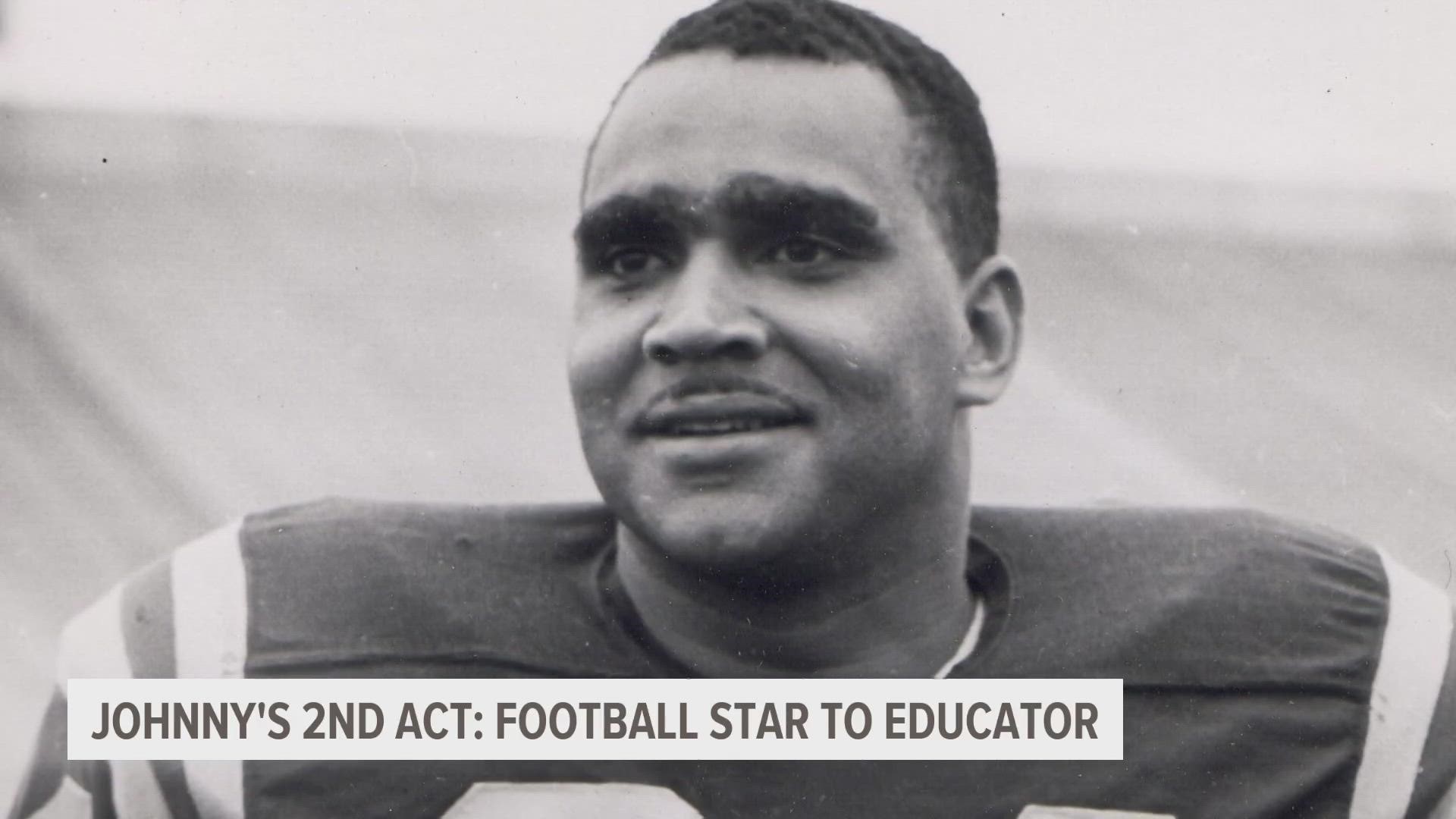

Johnny Bright

When an athlete's career comes to an end, there's often an assumption that it's the end of their story. But that's not really the case.

For Drake football great Johnny Bright, the end of his football career was the beginning of a new career dedicated to shaping young minds and serving others.

His legacy as an athlete and a scholar is held in high regard at his alma mater.

Bright was one of the most talented and successful football players of his time, even though discrimination and racism presented countless roadblocks throughout his career.

"Johnny had a commitment to himself that, 'I am going to succeed despite people trying to pull me down, people not wanting me to succeed,'" said Dolph Pulliam, former Drake basketball player.

Pulliam attended Drake in the late 1960s and got to meet Bright after his coach asked him to take Bright on a tour of the athletic facilities. Pulliam said he still thinks about the advice Bright gave him back then.

Bright's career began to take shape while at Drake University. He was a multi-sport athlete, but football was where he excelled the most.

During his sophomore season, he achieved his long-time goal of playing quarterback at the college level and totaled 1,950 yards — making him the first sophomore player ever to lead the NCAA in total yards for a single season.

He had another record-breaking season during his junior year and by his senior year and was considered a favorite to win the Heisman Trophy.

Despite being the school's star player, you couldn't tell by the way he was treated.

"Blacks were not allowed to live on campus. You couldn't eat your meals in the dining hall with the rest of the students. You weren't allowed to do that," Pulliam said. "So, they had to find rooms in the African American community for him to stay in, and they'd fix his meals and what have you, so that was his life."

Bright couldn't escape the prejudice on the football field either.

In what's known today as the Johnny Bright incident, his jaw was broken during a game against Oklahoma A&M in 1951 as a result of a vicious hit by an opposing player despite not even having the ball.

The incident led to major changes to NCAA rules, like the implementation of helmets with facemasks and cracking down on illegal blocks.

Even after the incident, there was no doubt that Bright was destined for a great pro football career.

But the football star also had his sights set on another dream of his.

"For him, athletic prowess opened the door to ongoing education, and he chose to study education when he came to Drake. So, it wasn't just he came to Drake to get an education, he already had the ambition of paying it forward," said Craig Owens, John Dee Bright College dean.

After college, Bright had a hall-of-fame career in the Canadian football league, with several records and awards to show for it.

But that's not where Bright's story ends.

By the time he decided to hang up his cleats for good, he was ready write the next chapter in his life.

"After the athletic career is done, Johnny got a second act," Owens said.

That second act would be just as impactful as his first.

After his retirement, Bright remained in Canada and began his career as a teacher.

He eventually worked his way up to becoming a principal within Edmonton Public Schools.

"The chance to be under the stadium lights, all eyes on you with the football making the big play. When that ends, Johnny turns his attention to something as demanding — arguably higher impact, but lower profile. But [he] never regrets having made that decision, never thinks this is a consolation prize," Owens said.

Bright spent almost two decades working in education up until his death at just 53 years old in 1983.

"It really feels like education, his career in education, was more like the culmination of a lifelong career rather than a coda or an addendum or an afterthought," Owens said.

Bright had made such a profound impact on his community that a school in Edmonton was named after him in 2010.

In 2020, Drake University named its new two-year associate's program after Bright.

In all aspects of his life, Bright was a shining example of grit, resilience and dedication.

"If you have a goal in mind, let that goal be a burning desire inside of your heart and in your mind and that no one is going to take that away from you. Johnny bright didn't let that happen to him," Pulliam said.

Almost four decades after his death, his life is still providing lessons that future generations can learn from.

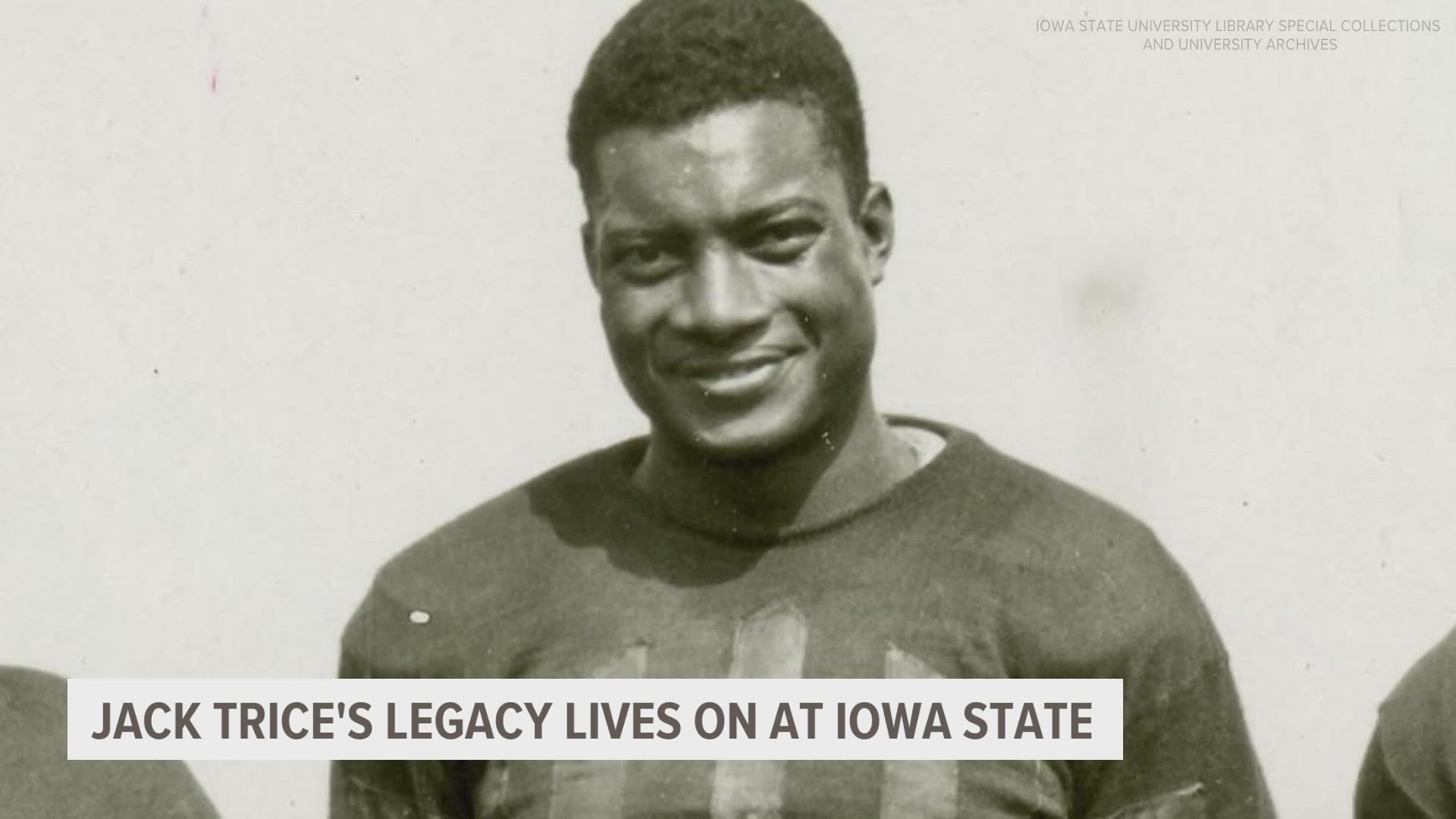

Jack Trice

Almost 100 years after his death, the story of Jack Trice, Iowa State University's first Black athlete, still resonates deeply with today's Cyclone athletes like O'Rien Vance, a former ISU linebacker.

"To bet on yourself when every single odd was against you. No one wanted him to be there on that field, no one wanted him to play football. To go out and be one of those ... guys that played on both sides [of the ball]," Vance said. "He was one of those guys that played on both sides of the ball. I mean, for me I also decided to go to Iowa State because it was named after one of the only African Americans, so to have that and to be able to play in Jack Trice Stadium meant the world to me."

Jack Trice exemplified courage and determination. He was driven to succeed not only for himself but to ultimately help others.

"He wanted to better himself," said Jonathan Gelber, author of "Idealist: Jack Trice and the Fight for a Forgotten College Football Legacy". "He wanted to use football as a way of getting an education even though there were no scholarships at the time."

In 1922, he began attending Iowa State. He studied animal husbandry, which deals with raising livestock and selective breeding.

His goal was to use what he learned to help Black farmers.

Outside of his studies, Trice was on the track and field team and joined the football team his sophomore year.

In the fall of 1923, Trice was set to play in what he considered his first real college football game.

The day before, he put his thoughts on paper in the now-famous letter.

Part of it reads, "The honor of my race, family and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part."

"Jack, when he was stepping out there, was not just representing himself, he was representing his family and the first thing he listed was his race," Gelber said. "A lot of people of color who I've interviewed, that's what they understand and I think that particularly resonates with them."

While inspiring, the letter was equal parts eerie, almost foreshadowing his own death.

On Oct. 6, 1923, Trice suffered serious injuries in the game against the University of Minnesota.

Those injuries would lead to his death just two days later.

As the years passed, the memory of Jack Trice faded from memory on the Iowa State campus — until the late 1950s.

Tom Emmerson was a reporter for the student newspaper, the Iowa State Daily, when he came across a plaque dedicated to Trice in a gym on campus.

Not familiar with who he was, Emmerson asked around and got filled in on Trice's story. But he wanted to know more.

"I would like to say I went immediately, but pretty close to immediately, to the library and asked to find out more about him," Emmerson said. " And that's where I got almost all the information for the story."

In 1957, he wrote an article about Trice that would spark new interest from students to bring Trice's story back to the forefront.

The article didn't generate buzz immediately though. In fact, it wasn't until the early 1970s that it resurfaced. By then, Emmerson had become a professor at the school and was actively working to educate students about Trice.

"The main thing we did [was] more or less establish an informal guerilla movement inside the journalism building and the idea was to keep the story alive," Emmerson said.

It worked.

Who Jack was and what he stood for resonated with students, and they felt that he should be honored.

"Iowa State had begun building its new stadium and one of the students said 'Jack Trice Stadium,' let's go for that," Emmerson said. "That was their focus."

Channeling the same "I will" mentality Trice expressed in his letter, the students persisted, and in 1997, they accomplished their goal.

It took almost a quarter century to get Trice's name on that stadium, but now, his legacy is immortalized for all to see.

While Trice's life was short, the impact he made is immeasurable.

"This ideal of Jack not only trailblazing in his lifetime, but inspiring a generation of students, and here we are 100 years later still talking about him," Gelber said.