Defining Progress | A community pulse check 1 year after the death of George Floyd

Local 5 breaks down the events surrounding George Floyd's death in Des Moines and what the community has done to move the needle forward.

George Floyd, a Black man, was murdered along the side of a street in Minneapolis by a police officer who held his knee along Floyd's neck for nine and a half minutes on May 25, 2020.

A Minnesota jury ruled Derek Chauvin was responsible for Floyd's death just one month ago, but last year, many feared Chauvin wouldn't be held accountable for his actions in the court of law.

So, they took to the streets, not just for Floyd, but for the countless Black Americans who are killed at the hands of police in the country every year, chanting "I can't breathe," "hands up, don't shoot" and "Black lives matter".

Floyd's death, captured on camera for the entire world to see, brought a greater sense of urgency to address police brutality in the United States.

While there have been many killed by the hands of police in this country, the fact that someone caught Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck brought it from lines in a news story to a video that can be viewed on numerous mobile platforms.

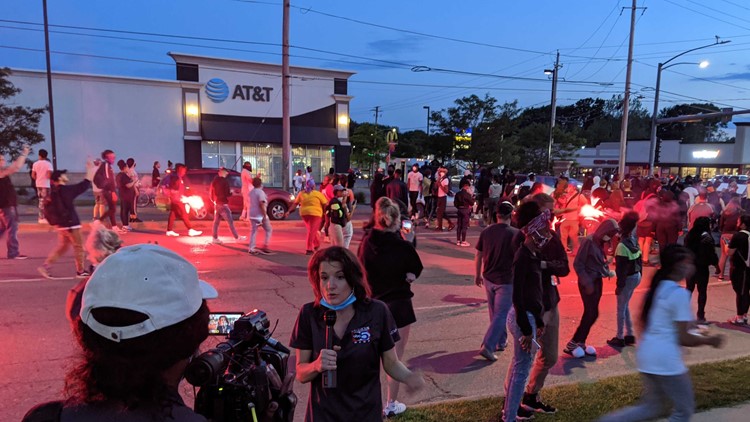

Protests sparked across the country within hours, the first in Des Moines happened just days following Floyd's death. Some turned violent among smaller groups, with demonstrators being tear-gassed and some police cars vandalized.

The calls for equity and equality for all grew louder and louder. Iowa worked to pass some legislation to address those calls, but advocates say even those aren't enough or are the complete opposite of what the state needs.

Iowans found during protests that they can serve their community immediately, without help from the government. They went from the bottom up, not the top down.

Local 5 is breaking down the events surrounding George Floyd's death in Des Moines and what the community has done to move the needle forward.

All photos: George Floyd Des Moines protest May 31, 2020

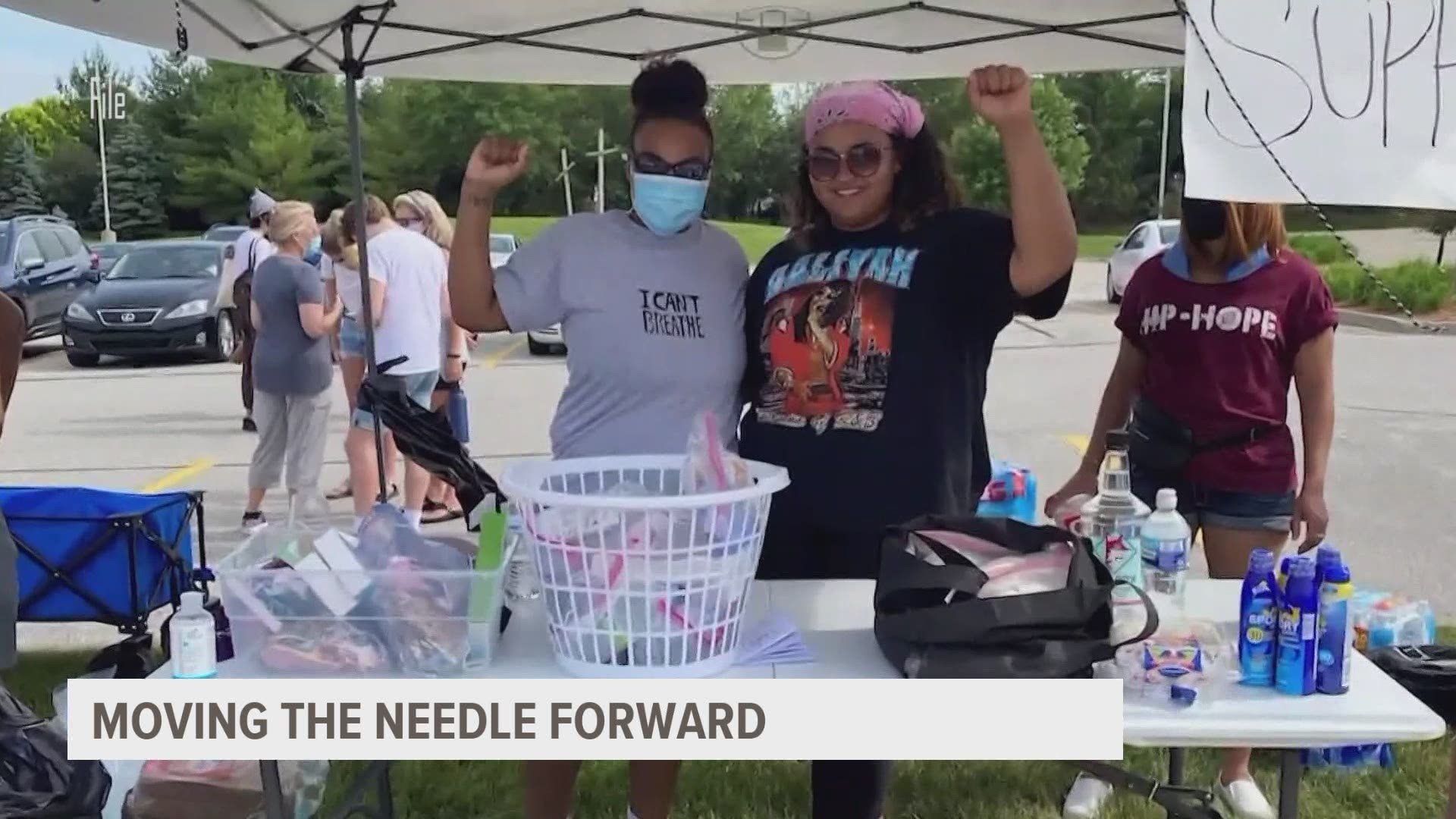

Protests died down, but the message still lives The Supply Hive

It started simple.

Food, water and first aid for protesters. Zakariyah Hill and Aaliya Quinn soon started calling themselves the "Supply Hive."

"Every day it was a bit of the same thing... You come in, bring your sign, you say the chants," said Hill. "Realistically protests are not forever. The summer of 2020 is not forever. However, there are things that can be."

Things that can move the needle forward. As protests died down in Des Moines, Hill and Quinn transitioned to carrying on the message of Black lives matter and equality in their own way.

"It's mutual aid. It's just cooperation and lending hands wherever they need to be," Hill said.

"Mutual aid" is a buzzword, but Hill and Quinn live and breathe their Supply Hive mission, gathering supplies for mothers, the most basic essentials to raise a child.

Creating access to free, healthy food through a community garden and making a space for people to take what they need, no questions asked, is the duty of Monika Owczarski and Cam Schneider.

"We're meeting people where they're at and providing them with resources to really nourish them on like a full spectrum," Owczarski said.

"There's a need for support there's a need for someone to step in…on the sidelines and say we got you we're here for you," Schneider said.

While the Supply Hive offers mutual aid, they can't move the needle on their own without community buy-in.

The support comes from other community members, like Katie Allen, who we got to know last year during the protests.

"I believed as a white person that our racial problems were taken care of 55 years ago…we are far far from that," Allen said.

Allen found other like-minded folks who grew up with similar backgrounds to figure out how they, too, could move the needle. She tries to be an ally for people of color.

But is having a conversation enough?

"No, it's not enough," Allen said. "I don't think I could do this for another 55 years if I live that long and anything that I do be enough."

It takes a whole community, the Supply Hive knows that, but it also involves the changing of policies for the better.

"When you have police in schools it really just leads to over-policing that disproportionately impacts students of color and students with disabilities," said American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa Director Mark Stringer. "In Iowa, a Black girl is nine times more likely to be arrested in school than a white girl."

This problem of systemic racism needs to be addressed, and the Supply Hive hopes their small amount of activism is helping move forward, one inch at a time.

"People do care about one another, but it comes down to showing up and how do you show that you care.," Hill said.

The complexity of wearing blue while Black Keith Onley's story with Polk County Sheriff's Office

Keith Onley, inspired by his school resource officer at Hoover High School, started as a detention officer at the Polk County Jail in 1997 and rose through the ranks to become lieutenant.

But seeing how the Black community is treated by law enforcement, and even in his own ranks, finally drove him to early retirement in 2020. The raw emotions still plague him a year after Floyd's death.

Onley, a Black man, dedicated his life to his community. He has the uniforms and medals to back it up. His 23 years at the Polk County Sheriff's Office brought him pride for the right reasons.

But for every life he saved, for every fond memory he experienced, is a greater sense of loss of what he felt his career could never be for someone like him.

"People that don't look like me don't understand the life that I've had to live within uniform," Onley told Local 5's Eva Andersen.

Being Black while wearing blue has always brought up complex feelings for Onley.

"I've had to teach my kids how to engage with law enforcement instead of just being treated as an equal," he said.

Unequal treatment Onley himself has faced. He spoke of a time his white friend was pulled over for not using a turn signal while he was riding as a passenger out of uniform. Onley said the officer asked him for his license.

"He came back to the passenger's side and I said, 'You didn't find anything did you?' He said, 'no.' That's because I work for the sheriff's office. And the guy says, 'Well why wouldn't you say that?' Would it matter? Why does it matter?" Onley said.

It's mistreatment that Onley is already too familiar with, and behavior that he trained his deputies to avoid when he was a supervisor.

"I would teach them [to] follow the policy. If you follow the policy, you can't go wrong," Onley said.

But as time wore on, Onley tired of what he described as not seeing change. He was only one of two Black, full-time deputies at the Polk County Sheriff's Office in his 23 years there. There were a few reserve officers.

Then 2020 hit, and it all escalated. Onley said he felt some deputies and officers unleashed disproportionate force and aggression on protesters.

The officers who did, Onley felt, became the loudest.

"In the law enforcement community, we have great officers," he said. "But it's the mavericks and the cowboys that work outside the lines that get the attention."

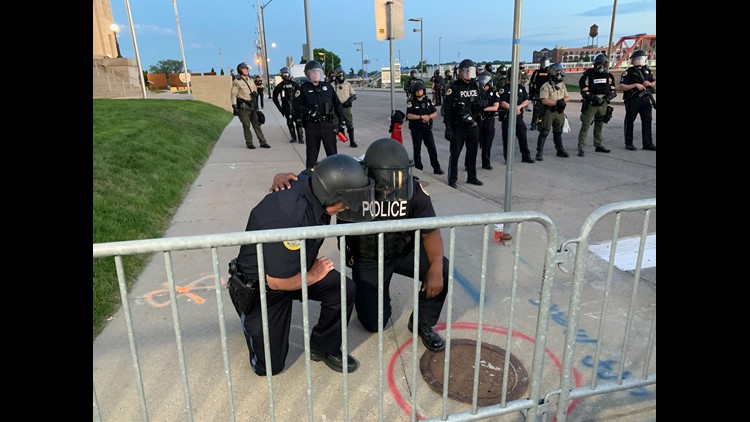

It all came to a head when Onley found himself in his riot gear to meet Des Moines activists.

"I understand exactly what each and every one of those protestors, Black lives matter. I understand their life," Onley said.

One night of the protests, a commander announced they were going to kneel with protesters, but what was said next broke Onley's will to keep going.

"The person next to me said, 'I'm not going to take a knee. We need to pepper spray them,'" Onley said through tears. "'We need to pepper spray them because I don't believe in taking a knee.'"

Onley said he broke down that night after stripping away his riot gear.

"He came home that night and it was as if something had been taken away from him," said Onley's wife Alisa. "But it was then that I saw the determination. We had talked about when he would retire, but it was the finality of what he went through."

After 23 years, Onley made the painful decision to hang up his uniforms. Onley had planned to serve for 30 years.

"I got in 23 years. I didn't want to retire," he said.

For now, Onley said he'll look for another job outside of law enforcement. A career he tried to change internally but felt he wasn't allowed to do so. He still thinks there is a solution.

"Law enforcement agencies should hire what's called a 'chief diversity officer' that reports directly to the chief of police," Onley said. "That oversees the office of professional standards, and oversees the recruitment process."

Although he's removed himself from law enforcement, Onley said he knows society's will to reform it will carry on.

"It's not going away," Onley said. "George Floyd did make a difference in this world."

The Polk County Sheriff's office tells Local 5, "Sheriff Schneider is striving to add more diversity to the Sheriff's office." They said they are currently working with the NAACP and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement (NOBLE) to recruit more Black deputies.

Currently, over 90% of deputies are white, 1.8% are Black, 1.8% are two or more races, 2.5% are Asian, and 3.7% are Hispanic.

When looking at all employees for the Sheriff's office, including correctional officers and security, the numbers are higher. More than 12% are minorities.

In the latest round of 55 applicants, 44 are white, seven are Black, three are Hispanic, and one is Asian.

They tell Local 5 at least four Hispanic deputies were just sworn in, and they hope to spread the word for more Black applicants to apply.

Demands made by the Des Moines Black Liberation Movement Were they met?

The Des Moines Black Liberation Movement sparked the call for change immediately after Floyd's death.

Over several months the group posted demands for the state and the City of Des Moines in an effort to address the unfair treatment of not only Black people but other minorities.

They demanded chokeholds be banned and for biased police be fired.

Sgt. Paul Parizek with the Des Moines Police Department said a lot of the demands made were already part of the department's policy. Chokeholds have been banned since the 1990s and an anti-bias policing policy has been in place since 2018.

The number one demand from DSM BLM at one point was to identify and fire all DMPD officers with violent records.

"We've got all the mechanisms in place to either address the bias or root it out," Parizek said. "That's not something someone needs to demand us to do. It's something we've been doing for quite some time."

Only DMPD Chief Dana Wingert can fire officers, but at one point his firing was a demand of DSM BLM. Only the city council and city manager are able to decide to fire the police chief, according to Parizek.

Local 5 attempted to reach out to the city council over two weeks for an interview, but no one wanted to talk. We also tried reaching out to DSM BLM, but members also declined interviews.

But outside the police department is a man named Ed Bloomer, who can be seen standing at the corner of Court Avenue and E 1st Street five days a week protesting.

"The cop that put his knee on the throat of George Floyd, I didn't know what in the world to think. Well, it was murder," Bloomer said. "We support [DSM BLM]. They're our allies. They're our friends. They're our neighbors."

Bloomer said he also thinks DMPD is doing a great job.

There are two demands that stay consistent here in Des Moines and across the country: Defund and abolish the police.

"Those are probably two of the most ridiculous," Parizek said. "In 2020, we responded to over 195,000 calls to service. Who's going to do that if the police aren't there?"

The city's budget for DMPD has increased by nearly $9 million over the last four years of records Local 5 was able to obtain. In the 2016-2017 fiscal year, the budget was over $61 million. For the 2019-2020 budget, it was over $70 million.

The DMPD has the most to spend compared to other city departments. For example, the Civil and Human Rights department had a budget of a little over $530,000 in the 2019-2020 fiscal year.

Legislative action What has been done in Iowa?

Iowa was one of the first states in the country to pass criminal reform following Floyd's death.

On June 12th, 2020, just days after George Floyd's death, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a law banning police use of chokeholds in most situations, made it illegal to rehire police officers who were fired for misconduct, and allows the Attorney General to investigate police misconduct.

The bill passed both chambers unanimously.

In August, Reynolds signed an executive order restoring voting rights to felons. Before the signing, Iowa was the only state in the country with a lifetime ban prohibiting felons from voting.

This month, lawmakers passed Senate File 342, also known as the "Back the Blue" bill, which would bring tougher penalties for rioters and stronger protections for law enforcement. The bill is waiting for the governor's signature.