DES MOINES, Iowa — A new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows increases in greenhouse gases are unequivocally caused by human activities.

Global surface temperatures in the past 20 years were nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the average from 1850 to 1900.

Temperatures are forecast to rise an additional 2.5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century.

From melting polar ice caps to rising sea levels to extreme weather patterns, our planet is already experiencing the severe impacts of climate change.

It's not just having an effect on coastal communities or far away places, though.

Climate change is having noticeable impacts right here in Iowa.

Consider water quality, for example.

At first glance, water quality and climate change may not have an obvious connection, but there is one.

It starts with water runoff.

When water moves from farmland to rivers and streams, it carries nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus with it.

Heavier rain events typically result in excess nutrients in Iowa's waterways, negatively affecting water quality.

So where's the connection to climate change?

Scientific data shows climate change is causing more heavy rain events in Iowa and across the Midwest.

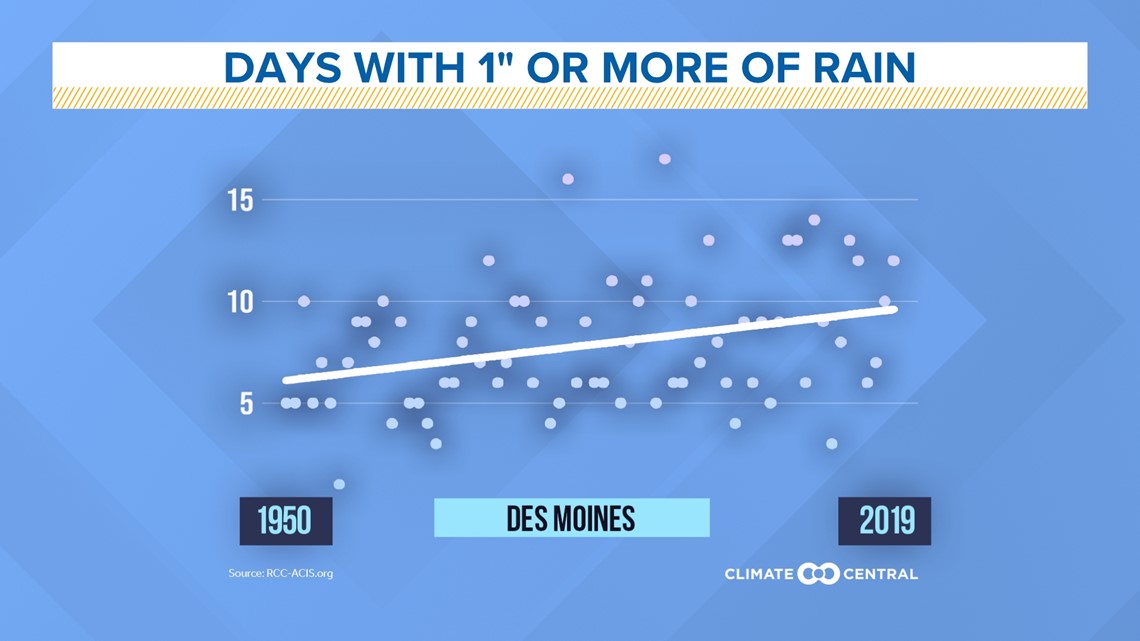

In fact, Des Moines is averaging about 4 more days per year with an inch or more of rain than it did in 1950.

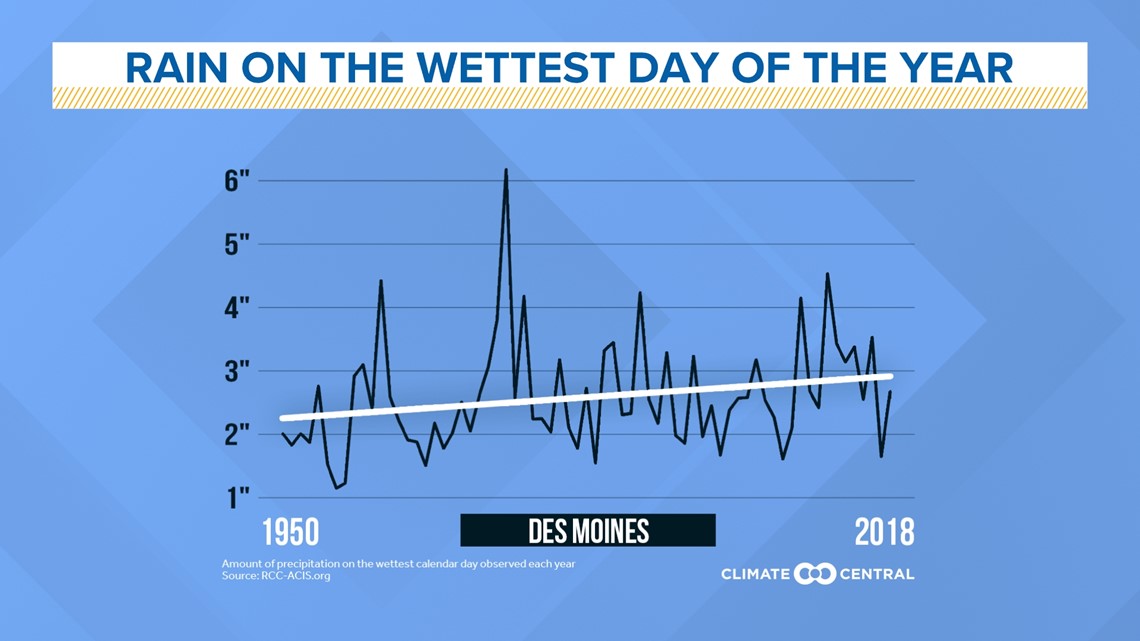

The rainiest days of the year are also getting wetter as time goes on.

A recent Iowa State University study found heavy rain events from only a few days of the year account for up to a third of the Mississippi River Basin's annual nitrogen runoff.

Background on the fight to improve water quality

Every year, nutrient runoff from Iowa and other states in the Mississippi River Basin spills into the Gulf of Mexico, creating an area known as the dead zone.

"There are excess nutrients that allow algae to grow and bloom really quickly, and when those algae die they take up all the oxygen in the water," said Alicia Vasto, Water Program Associate Director at Iowa Environmental Council. "That kills all the fish and other living organisms in the water and doesn't allow anything to grow there because it is a deoxygenated zone."

At an average size over 5,000 square miles - roughly a tenth of the size of Iowa - this dead zone is the second largest in the world.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the dead zone costs U.S. seafood and tourism industries roughly $82 million a year.

In 2008, 12 states in the Mississippi River Basin including Iowa finalized an action plan with the goal of a 45% nutrient reduction in the Gulf of Mexico by 2035.

Five years later, the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy was born.

Is the plan working?

Harmful nutrients in the water come from a variety of sources, such as wastewater treatment plants, industrial facilities, and farms.

Wastewater treatment plants and industrial facilities have made some promising progress, but agriculture is still struggling and is actually responsible for the majority of Iowa's nutrient loss.

Iowa's Nutrient Reduction Strategy outlines ways farmers can reduce nutrient loss on their property like rotating crops, reducing tillage, and closely monitoring fertilizer application.

The most effective practice so far? Permanent structures built on the edge of fields like terraces, saturated buffers, and wetlands.

Through a partnership with the state of Iowa, Dallas County farmer Timothy Minton added wetlands to his property, effectively reducing nutrient loss by 52 percent.

"From a conservationist stand point, it is just the right thing to do," said Minton.

The problem is there aren't many of these wetlands in place yet.

Only about 100 private wetlands have been installed through the partnership since 2003.

That number falls short of the Nutrient Reduction Strategy's goals.

"One of the scenarios the strategy lays out calls for 4,000 wetlands," said Adam Schnieders, Water Quality Resource Coordinator with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. "You have to engineer, design, work with landowners to locate and find the opportunities for these wetlands. If we were to build a wetland every single day, it would take us 11 years to just build that many wetlands."

Critics of the strategy say things need to change.

"The science itself is strong, but without a strong strategy to actually implement the ideas that are in it is not going to improve our water quality," said Vasto.

The state's nutrient runoff varies based largely on how much rain we get.

Even with the year-to-year fluctuations, Iowa's five-year running average of nitrate loads in 2020 was nearly twice as high as 2003.

The Clean Water Act has the authority to regulate pollution and runoff from wastewater and industrial sources, but not agriculture.

Some believe agriculture practices highlighted in the nutrient reduction strategy should be mandatory, not voluntary.

"There are a lot of very basic standards of care that should be required of all operators," said Vasto. "A very basic one would be having a buffer so you can't farm right up to the edge of a stream. We should also be regulating the amount of fertilizer that is applied to farm fields."

What happens next?

Unlike the Gulf of Mexico, there is no established timeline for Iowa to reach its nutrient reduction goals.

"We track progress with what is called a logic model," says Schnieders. "Logic models are typically used because you are expecting a long-time horizon to achieve these goals. Before we can see a change in the water, we need to see a change in the landscape. Before we see a change in the landscape, we need to see a change in what people are planning for and doing. Before we see a change in people, we need to see a change in the inputs provided like funding, staff resources and programs to participate in."

In 2018, the Iowa Legislature passed new legislation that provides more than $270 million for water quality efforts in Iowa over 12 years.

In 2021, state legislators passed a 10-year extension which secures more than $320 million in funding to help support the state’s water quality efforts through 2039.

An estimated $4 to 6 billion are needed to support everything outlined in the strategy.

"One of the key things to understand is that it doesn't all have to be in one year." said Schnieders. "You are investing in these things over time and they have design lives and can help for a long period of time."

Moving forward, the state plans to continue researching ways to improve water quality and specifically focus funding and resources toward nitrogen reduction.

"I think we are seeing a lot of good things moving forward as far as implementation of the strategy," said Schnieders. "Everyone wants to see the pace and scale of this work increase."

When asked whether or not nutrient reduction practices should remain voluntary, Gov. Kim Reynolds said, "I do because we are showing progress. We are showing increases in the number of participants and there is a lot of interest out there. At this point I believe that is the best path forward."