PRAIRIE CITY, Iowa — All Iowa drivers have seen them — and some may have been caught by one: Speed and red light cameras on interstates, highways and downtown streets are commonplace across the state.

Iowa Sen. Brad Zaun has been trying to get rid of automated traffic enforcement for more than a decade now, with pending legislation aiming to regulate or even ban ATEs.

While some people claim ATEs are about safety, others argue they’re a cash grab. Either way, ATEs seem to be a growing trend in Iowa.

According to the Iowa Department of Transportation, there's been a significant increase in the number of communities using speed cameras in the last few years. This is based on the number of requests that go through the DOT, which includes cameras placed on interstates, U.S. routes and Iowa routes. The DOT does not have data on the number of cameras on city and county roads.

"If you’re breaking the law, you’re breaking the law," Prairie City Police Chief Kevin Gott said.

That’s the simple purpose of an ATE camera: To catch traffic law violations.

Gott compares ATE citations to getting a parking ticket since they are civil violations, meaning they don't go on your record nor impact your insurance.

You can find them in in big cities like Des Moines and in small places like Prairie City — a city so small it has zero red lights, three full-time employees on the police force and four ATEs. Two at the school, one on the highway and one mobile ATE manned by officers.

Prairie City's not alone. According to data from the Legislative Services Agency, at least 25 local governments throughout the state use them.

But there’s some debate: Are they more about safety, or making a quick buck?

“That’s a county road that comes in and, when they did a speed study, we were having people going 40 or 50 miles per hour coming into town in a 25 school zone," Gott said.

The money gained from the citations is split between a private vendor and the city. And ATEs are bringing in a lot of cash.

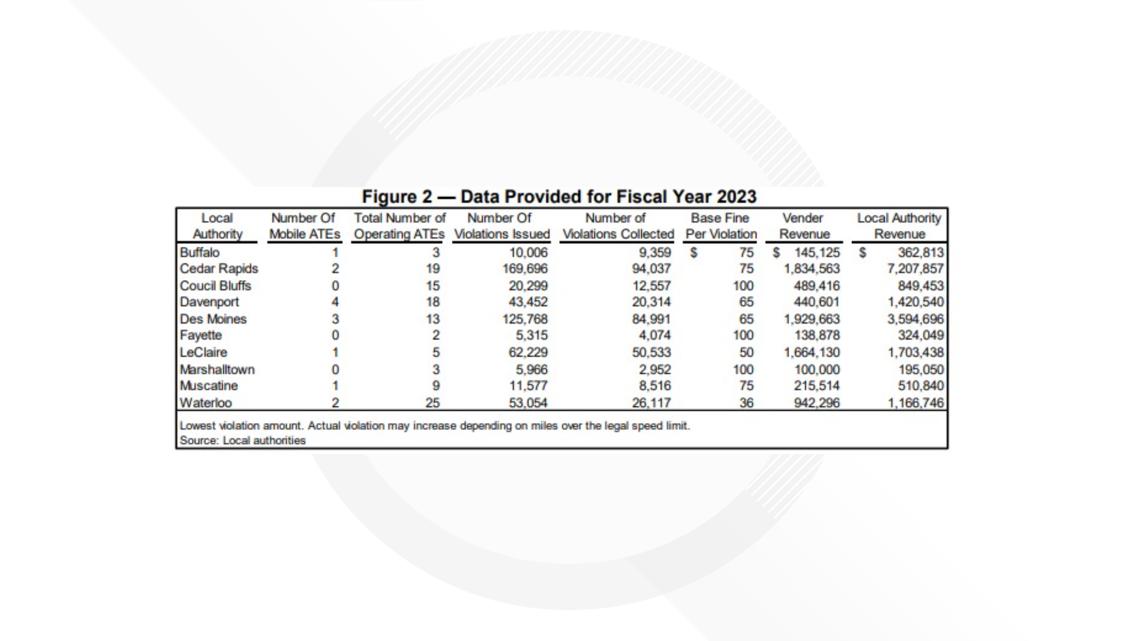

In the 2023 fiscal year, the city of Des Moines raked in around $3.6 million from ATE violations, while Cedar Rapids got about $7.2 million, according to LSA data.

Prairie City's police chief told Local 5 ATEs earned the city about $2.2 million in the 2023 FY.

“I just think that they’ve become more about revenue," Zaun said.

“Our base fine is $100, and that is from 11-15 over. Sixteen and above is $150," Gott said.

More than 11 over the speed limit is the unwritten standard for law enforcement pulling people over, according to Gott. The police department changed the ATE trigger from ten to eleven mid-2023.

Gott said 60% of ATE ticket revenue goes to Prairie City, and 40% goes to the private vendor that maintains the cameras, covers the cost of equipment and deals with back-end tasks like billing.

To put that into perspective, money from traditional citations is distributed differently. According to the Iowa Judicial Branch communications team, 80% of the fine goes to the city then court costs and surcharges go to the state for municipal speeding citations. For a county speeding citation, all of the money goes to the state.

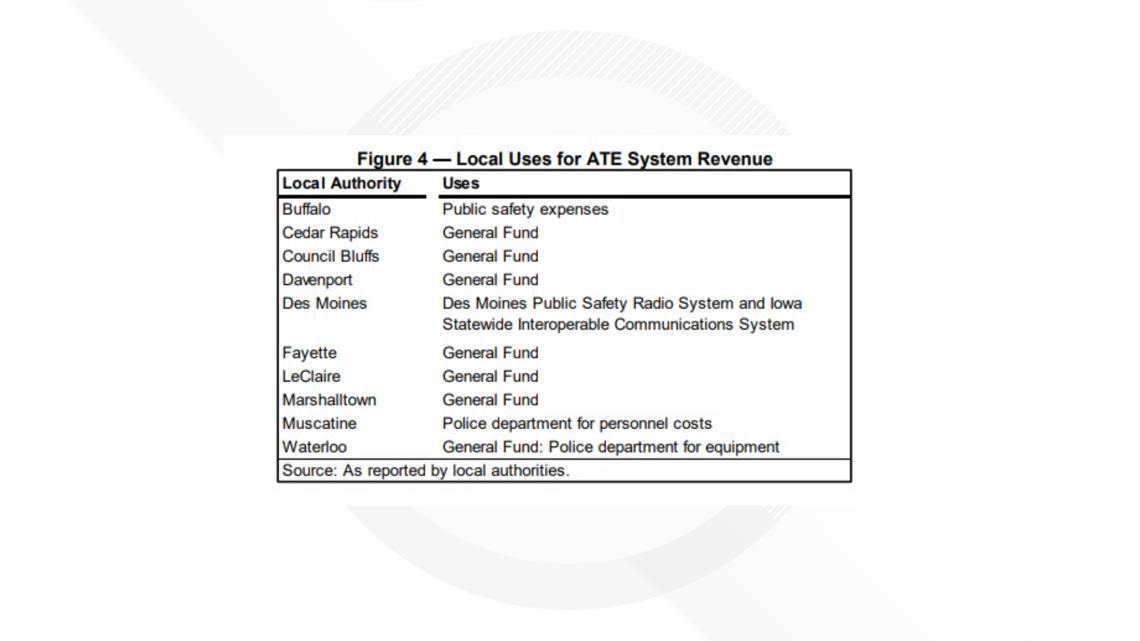

Like a majority of the ten Iowa cities that reported numbers to the LSA, Gott says Prairie City puts its citation revenue into a general fund.

“These funds are going straight back into the city to allow for improvements, growths, that type of thing that really benefits the people of the community and the surrounding area," he said.

Those improvements include projects like installing new water lines and building a new fire station.

Prairie City Mayor Chad Alleger told Local 5 that this revenue has been a big deal, as it's helped the town tackle large projects faster.

Without ATE money, the town would have to fund projects other ways like increasing the property tax levy or utility rates.

Whether it’s helping pay for big city projects or improving public safety, Gott says the cameras are making a difference for the community.

“Previously we were getting 20 or 30 violations a day in the school area. Now we’re down to maybe one or two a day," he said, adding that they've seen a difference in speeding on the highway, too.

Gott claimed ATEs help his department keep a constant and watchful eye on the road.

“We’re a three full time officer department," he said. "We can’t dedicate 100% of our time for speed enforcement."

Gott says their A.T.E.’s aren’t about a "gotcha" moment: They have photo enforced speed limit notices on city limit speed signs as well as several radar displays to show drivers how fast they're going.

A majority of the violations Prairie City catches with its speed cameras are from people out of the area, according to Gott. Still, with all the signage out, he said there's no excuse for breaking the law.

“We’ve made it as the best we can to try to show you that hey here’s what the speeds are through here. If you can’t see that flashing sign that tells you what your vehicle’s speed is, and you don’t know that the big white sign with numbers on it is what you’re supposed to go, we can’t help you," he said.

According to the Iowa DOT, revenue tends to be significantly higher with speed cameras on the interstate due to the amount of traffic as well as the amount of people driving through who are not from the area.

Compared to the rest of the country, Iowa is in a unique spot regarding its use of ATEs, with the DOT confirming Iowa is the only state in the U.S. with permanent speed cameras on interstates 24/7.

ATE critics like Zaun have other concerns with the cameras: Citations go to the car owner, even if they weren’t the person driving, and drivers are unable to confront their accuser like they do in traditional citations, even if they can contest the citations in court.

Zaun clarified that, while the ATE ban bill does not currently include exceptions in its language, multiple have been in discussion. For instance, exceptions for school and construction zones. This bill also ropes in hands-free legislation, which would ban the use of any electronic device while driving.

Some of the lobbyists supporting the legislation include Iowa State Sheriff and Deputies Association, Iowa State Troopers Association, State Police Officers Council and the State Police Officers Council.

Some of the lobbyists against the legislation include the city of Des Moines, the city of Cedar Rapids and the Iowa Police Chief Association.

For a full list of lobbyists on both sides of the legislation, click here.

Other bills in the legislature regulating ATEs include House Study Bill 161 and Senate File 489. Some regulations proposed include requiring local jurisdictions to get Department of Transportation approval to install ATEs, limiting how expensive fines can be and requiring signage notifying people of upcoming speed cameras.

The Des Moines Police Department sent Local 5 News the following statement regarding its use of ATEs:

"Automated traffic enforcement, when administered the right way and for the right reasons, is a highly effective traffic safety tool. Data driven implementation with the goal of reducing crashes at our most dangerous intersections, and/or addressing dangerous speeds in areas that are difficult to enforce by traditional means, can certainly reduce the likelihood of serious injury and fatality accidents. Our mobile system is almost entirely complaint driven, with locations requested by our citizens to address specific excessive speed issues in neighborhood throughout our community. Excessive speed has historically been our most common complaint, and the mobile units allow us to address the concerns of our citizens without drawing resources away from other emergency calls for service.

At the Des Moines Police Department, we have taken it upon ourselves to collect and analyze the effectiveness of our program, not just in terms of citations issued, by the impact the cameras have of the crash data, including the severity of the accidents. As with any operational program, the desired results must be measured to determine effectiveness and justification."